A Faculty and Model of Higher Education for the Lutheran University

Russ Moulds, Ph.D., Editor, Issues in Christian Education; responses from Charles Blanco, Gabriel Haley, and Brian Friedrich

Russ.Moulds@cune.edu

To the reader: This article takes a big bite of the apple—perhaps too big. However, including at once this set of topics—students, approaches to higher education, and faculty formation—may serve the reader by presenting sufficient scope to provoke further discussion rather than waiting on a series of installment articles. To get that discussion started, we include three thoughtful responses. The authors are confident that readers can generate the needed additional content and questions.

What sort of Lutheran college faculty can teach and form a signal population of influential Christians for church and world today in a culture which is now ambivalent (and perhaps sometimes hostile) toward religion, and no longer defers to a Christian perspective? Such teaching and formation is now the station and role of Lutheran higher education, and we must wonder if we are up to this task.[1] Right now the answer is: maybe.

Notice these opening sentences are loaded with the language of vocation—station, role, formation, task—appropriate for a discussion of Christian education that is Lutheran.[2] But vocation is not enough.[3] The concept of vocation, versatile as it is in Lutheran theology, is necessary but not sufficient. Much of our literature has helpfully explored and applied the theme of vocation to Lutheran higher education, so we need not rehearse the doctrine here.[4] We must include it, but to adequately and positively profile a Lutheran faculty, we also need to sketch out these additional elements: 1) our students’ culture; 2) a coherent rationale and model for higher education that is Lutheran; 3) the formation of a faculty and faculty member; and 4) a delivery vehicle for instruction that is congruent with our rationale and identity and that actually delivers to students an education which forms them as Christians in the world and their culture today. Along with vocation, each of these elements for faculty formation deserves a chapter in a book. We’ll settle now for just this sketch.

Our Students’ Culture and Sub-cultures

C.S. Lewis argues in The Abolition of Man, which many consider his most important book, that the irony of human culture is that it does not affirm humanity (as culture purports to do) but abolishes our humanity by constantly directing us away from God and only to ourselves.[5] In this respect, our task as a Christian university is to help students critique their culture and its sub-cultures—Snapchat, Instagram, Twitter, CRISPR, sports, music, red politics, blue politics, et al—and, in doing so, to conduct students some distance away from their culture. Only then can they avoid culture-capture and learn to re-evaluate it in the light of God’s Word. The aim is not to condemn culture, nor merely accommodate it, but realize its condition and devise ways to bring to our culture some genuine Good News (cf. 1 Corinthians 9:19–23).[6]

At this writing, we have now concluded another presidential election, and thoughtful observers among us are trying to assess what its outcome and politics now mean for our culture and the church. There’s not much new under the sun, and we should not become excessively animated—pro or con—about current events since they won’t remain current. Our teaching perspective always includes Isaiah 40, He sits above the circle of the earth, and we are like grasshoppers; and Psalm 46, God speaks and the earth melts.[7]

Yet, as citizens in both God’s left-hand kingdom and his right-hand kingdom, we do need to pay attention to the current scene. The professions, politics, arts, and sciences are important parts of our students’ culture and their future that we are to help them understand.

Faculties, astute though they are, have tendencies to mis-teach about the culture. We may teach out of our own cultural background, the one that shaped us in a generation already passing or past. Or as young professors, we teach our graduate school and our discipline’s version of culture along with our preferred current cultural trends, not yet noticing our blind spots and that these preferences are already moving into the rear-view mirror. Or, perhaps mid-career, we’ve figured out the wisdom of the antiquities or an important established tradition and seek to induct both students and colleagues into this enduring ethos, but without accounting for that person’s cultural context.

We can certainly use our own orientations to culture as devices to assist students. For instance, we can use our own engagement with the world, recent or recently past, to familiarize and orient students to some of the ways the world has worked or not worked very well. And we can even more productively engage students in a genuine tradition such as the liberal arts of antiquity, or the Reformation’s powerful insights about the Gospel—what Elert calls the Lutheran ethos[8]—or, better yet, craft both into a curriculum. (See the essays by Scott Ashmon on this important project.[9]) But any of these three modes alone—or even all together—will leave students in culture-capture of some kind, whether ancient, recently past, or current.

So, like our students, we as a faculty are susceptible to certain kinds of culture-capture. One sort of captivity for us comes from the sub-culture of higher education itself. Higher education has taken on an assortment of manifestations, approaches that might be categorized in these five models or modes:[10]

- The multi-versity: the research-industrial campuses with large tax bases or endowments whose assorted departments and programs are not integrally related

- The college experience: the smaller campuses which seek to create value by packaging a community life for post-secondary adolescents transitioning into adulthood

- The university: the campuses (generally smaller) that sustain a knowledge-and-learning orientation, usually integrated within an academic tradition, and seek to induct young people into the way of life unified by that tradition

- The drive-by degree program: the campuses that provide utilitarian degree programs for employees and students who must work fulltime

- The correspondence school: the online programs, MOOCs, and other variations of non-classroom content delivery

In a diverse society, each of these models may have its place,[11] and we need not denigrate any of them. But in our age of both culture shift and inevitable revision of higher education, a Christian college can too easily mismatch itself to a model that is not conducive to its mission and ministry. Of these five, we can contrast the university model (which, when used wisely and well, sustains a creative tension between God’s two kingdoms) particularly with the college experience model (which, when adopted without critique, tends toward contemporary cultural conformity).[12]

A Coherent Rationale and Model

Go to the “About” page on the websites of several respected Christian colleges, and you will find thoughtful, well-crafted, biblically sound statements of mission, vision, and core values (henceforth MVVs). These MVVs are a helpful response and hedge against the late 20th century erosion of Christian identity on many campuses. With his 1998 book, The Dying of the Light, James Burtchaell ushered in a body of literature that examines what John Henry Newman called “the idea of a university” for Christian higher education. The concern of Burtchaell (and similar studies) is the process that corrodes the bonds between a Christian college and its theology and mission, how the college’s Christian identity becomes first marginalized (often imperceptibly), then expendable, and finally dismissed. Many, though not all, Christian colleges have heeded the alert and shored up their institutional documents, and this is a helpful step.[13]

A deficit remains, however, on many campuses between these MVVs and delivering the goods. This is not to say that students lack good instruction from faithful professors and positive experiences from student services. The concern is not about quality teaching and content, or about student activities in a Christian community. What often seems to be missing is a working rationale that connects the purpose and aims of the university to the purpose, aims, and learning of students in ways that the student can access and understand.

And this is not to say that many of our students fail to make those connections. Our more able students who contemplate the synthesis between an institution’s MVV statement and their own particular educational experience may well be able to see the congruence between the two. Yet, how many students, even the brightest and the best, will engage in such contemplation on their own? It is not the student’s task to discover the congruence between an institution’s MVV statements and how that institution carries out its educational task. Rather, it is the project of the institution’s faculty and administration to make sure such congruence is in place where students will encounter and understand it: across recruitment, classrooms, student housing, student activities and athletics, and student services.

However, if the connections between the MVV statements and the student’s experiences are more random and serendipitous than genuinely curricular and intentionally devised, then it will be much less likely that students will be able to articulate how they are receiving a Christian higher education across the various domains of the institution, and then carry that education into the world. That MVV needs to be evident not merely within the statement but as students proceed through a coherent course of studies and other activities to arrive at the insights and outcomes that the university has set for them.[14]

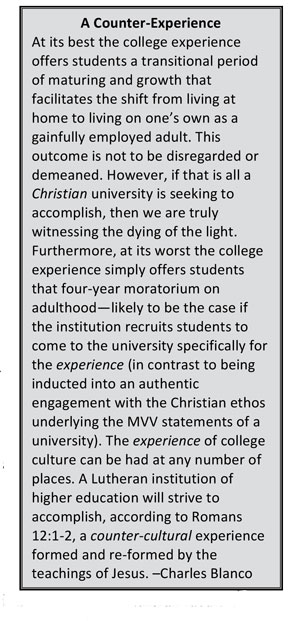

Some readers may hesitate at the preceding clause, “that the university has set for them,” but it marks an essential distinction for a Lutheran faculty and every Christian faculty: the distinction between a college experience model of higher education and a university model of higher education. In the MVVs of Christian and Lutheran colleges, we often see references to “distinctives” which claim a theological tradition that sets that school apart and separates it from the culture. However, in our society which takes consumerism for granted in all things, including higher education, the college experience model actually prevails on most campuses.[15]

A Google search of “the college experience” generates pages of direct hits, and the Urban Dictionary mocks the college experience as “one of the biggest clichés out there.” “The college experience” refers to an array of events, activities, and experiences available to older adolescents during their undergraduate college years that includes academics but are largely social and cultural. Some of these experiences are prescribed or offered by the college itself (e.g., First Year Experience groups and service learning), but most—good and not-so-good—are prescribed by the culture.[16]

Students believe that they make choices about the experiences available to them, but they are more often inducted into their experiences by the social forces they do not yet recognize or understand.[17] Again, this is culture-capture. William Willimon anticipated this challenge for the church and its education 30 years ago: “Decisions are fine. But decisions that are not reinforced and reformed by the community tend to be short-lived. A Christianity without Christian formation is no match for the powerful social forces at work within our society.”[18]

Many schools use the college experience model because our diverse and democratic society demands it, it makes a good fit with our consumer economy, and it attracts students and families who have no other basis for making a college selection. Thus, the cultural and financial realties for the small Christian college make this model hard to resist.

However, the college experience lacks any rationale beyond the consumerism of a culturally expected and generic collection of some majors, activities, and social (but not always judicious) experiences for late adolescence. By contrast, a university model provides a rationale that coherently connects the mission, ministry, and core values of a Christian college to its academics and other dimensions of Christian community. And it does this in ways that students can apprehend and internalize—that is, learn.

By definition, a university is a universitas magistrorum et scholarium, or “teachers and students turned toward one rationale as a learning community.” The Christian university does not seek to be a consumer campus for all customers. Rather, in its concern for the world God so loves (including consumers), it exists to induct students not into whatever the student chooses but into a certain version of life. A Lutheran starter rationale, then, could well be “to know Christ and him crucified” (1 Corinthians 2:2) and then to elaborate a university model and its liberal arts curriculum from that theme. Other key biblical and Reformation themes might be used, but the point is that the Christian and Lutheran university provides students with what they will not receive in a college experience model: a well-worked-out framework across the curriculum and their other activities. By means of a rationale that is congruent with the university’s identity and its MVV, students can meaningfully interpret their life and the fallen world God has acted to redeem, and then enter their culture as a signal population of influential Christians for church and world.

This rationale then informs the curriculum in meaningful and practical ways, not just as front office window dressing in the MVVs or as assessment wallpaper, though not as draconian constraints on content, either. We can do better than those alternatives. For purposes of our brief sketch, a Lutheran university could, for example, draft a rationale around these four key Reformation insights about the Gospel: a biblical anthropology of human nature, vocation, Christian liberty, and the two kingdoms. Other versions could be applicable, depending on that university’s resources, constituency, and opportunities.

However, to do this, we need an institution willing to be a university and a faculty patiently able to work out such a rationale and put their university model to work.

Faculty Formation

In 1 Corinthians 7:29–31, Paul insists that the form of this world is passing away. In Romans 12:2, Paul encourages us not to be conformed to this world. He is, of course, correct on both counts. In Romans, he gives us this counsel after several chapters that explain why in the world we need encouragement to be transformed by the renewal of our minds. And so we pause to reflect on being “in the world but not of the world.”

We, as faculty, continually reflect on what it takes to re-form (semper reformanda) ourselves as a faculty—a faculty that can be about the formation of students as Christians in a culture that no longer gives religion a free pass, but still a culture of souls Christ seeks to redeem. We are concerned for our own formation with the same concern Paul expresses about the Galatian church in their culture: “I am in travail until Christ be formed in you” (Galatians 4:19).[19]

In order to fashion and practice a coherent rationale of Word and Spirit as a Christian university,[20] a Lutheran college faculty must be formed, not just called (much less merely employed and ready to move to a greener pasture). Luther’s phrase applies well: “calls [but also], gathers, enlightens, and sanctifies.”[21] The aim of the Christian university and its faculty is the turning (versus) and forming of students to one (uni)—that is, one unified and coherent—ethos of life, reality, and purpose. The university designs to induct students into its MVV and rationale such that students can grasp and internalize them. By this manner of higher education, students can compare their university ethos with other claims and rationales in culture about which we also must teach and they must also learn. The faculty wittingly (not incidentally or accidentally) prepares our students to carry these MVVs and way of life out into their culture as a blessing to that culture, addressing needs that culture may not be aware of (cf. Genesis 12:1–3).

In today’s culture, this is a tall order for a faculty. It amounts to this: that the faculty view itself as a body of scholars who see the necessity of themselves being regularly formed and re-formed “in, with, and under” the working rationale of the distinctives referenced above. It calls for the faculty to agree that, while the vocabulary of “terminal degree” may apply within one’s academic field, it most certainly does not apply within the vocational role of carrying out the MVV statements that focus on the formation of students to serve church and world. In that calling, there is no terminus, but as noted above semper reformanda. Members of such a faculty and administration will, by the calling of the cross, resist the potential for any pride-of-place and will instead strive to carry out their tasks with and among colleagues, staff, and students in a manner of humility. This is a challenging tension to maintain: to be, on the one hand, bold enough to say, We have the faith and ethos “once for all delivered to the saints (Jude 3) while at the same time confessing to and with their students, “Lord, I believe; help my unbelief” (Mk. 9:24).

We can now better see why a college experience model won’t work well for a Lutheran or other Christian faculty. The typical college-experience campus lacks any meaningful, well-worked-out rationale, does not conduct student experiences according to any historically extended, socially embodied tradition or way of life, leaves experiences to the random disposal of consumer-students, and does not move students toward any coherent outcome or life meaning. The college experience simply offers students a four-year moratorium on the transition from older adolescence to young adulthood.

We can now better see why a college experience model won’t work well for a Lutheran or other Christian faculty. The typical college-experience campus lacks any meaningful, well-worked-out rationale, does not conduct student experiences according to any historically extended, socially embodied tradition or way of life, leaves experiences to the random disposal of consumer-students, and does not move students toward any coherent outcome or life meaning. The college experience simply offers students a four-year moratorium on the transition from older adolescence to young adulthood.

The teaching and ministry of a Lutheran faculty does more. By our practices in the arts, sciences, and humanities, we compare, contrast, and connect our campus and curriculum to culture. The faculty that is Lutheran enables students to recognize their culture as yet another variation of the biblical fall (Genesis 3-11, Romans 1–8). In response to this mis-shaping of humanity and creation, students will be shaped to see clearly how the fulfilled promise of Christ made flesh, crucified, and risen alters how we operate in both the left and right-hand kingdoms for the benefit of all whom they will encounter. A faculty which conducts a different sort of education may be a community of capable scholars, well-suited to its manner of higher education–but it is simply not a Lutheran faculty.[22]

The world our students enter is not simple. Correspondingly, our Reformation framework, in place centuries before our students entered this world, is not simple. The Reformation framework shaped by God’s revelation in His Word and finding its fullness in the Word-Made-Flesh is multi-plex. It includes both justification and sanctification. It will be misunderstood if one focuses only on the right or left hand kingdom without taking cognizance of the other. It has both an appropriate pessimism about the human condition as well as the highest optimism for humanity redeemed in Christ. It speaks a word of Law that condemns sin even as it holds out grace and mercy so deep and restoring as to bring hope to the most hopeless conditions.

While multi-plex, however, it is certainly teachable and apprehensible. Our teaching ministry to our students is, as a faculty, to craft a university rationale derived from this formidable theological tradition. That rationale is sufficiently complex to apprehend a messy world, and we translate it to our curriculum in ways that are attainable for the undergraduate. This is why we call it higher education.

None of our précis here on faculty formation is to imply that we have some algorithm for such formation. Rather, the Lutheran ethos is a powerful and versatile framework for fashioning many educational strategies—while always under the cross, located in our array of Reformation insights about the Gospel, and applicable in inventive ways to the changing world. Across our disciplines and through co-curricular events, we present students with examples of how our lives and our culture are replete with spiritually loaded incidents and intersections between God’s left-hand kingdom and his right-hand kingdom. We help students see and properly act upon connections between the “secular” and the “sacred,” positive law and revealed truth, human reason and divine mystery, and society and the church. [23]

We do this work in our courses not as instructional add-ons or as afterthoughts, as though what God is doing in Christ is extra-curricular, an aside, or optional. And as important as chapel is to regularly marking our identity with Word and Sacrament, worship is not our forum for the work of higher learning.[24] We do our work in classes and curriculum because the incarnation, crucifixion, and resurrection are central to all that we teach about life and reality. We do it because, however we fashion our university rationale, Christ is central to that curriculum model and rationale, not just boilerplate in our MVV documents. Or, to put it as many of us learned in our left-hand kingdom graduate program, we need to operationalize our MVV terms.

Our treatment here is brief, but we can suggest the contours of formation for a faculty that delivers on its edition of a Lutheran rationale. What follows would be equally important to apply to those who engage in student life services and in coaching. One way to sketch this out is from the point of view of a younger faculty member:

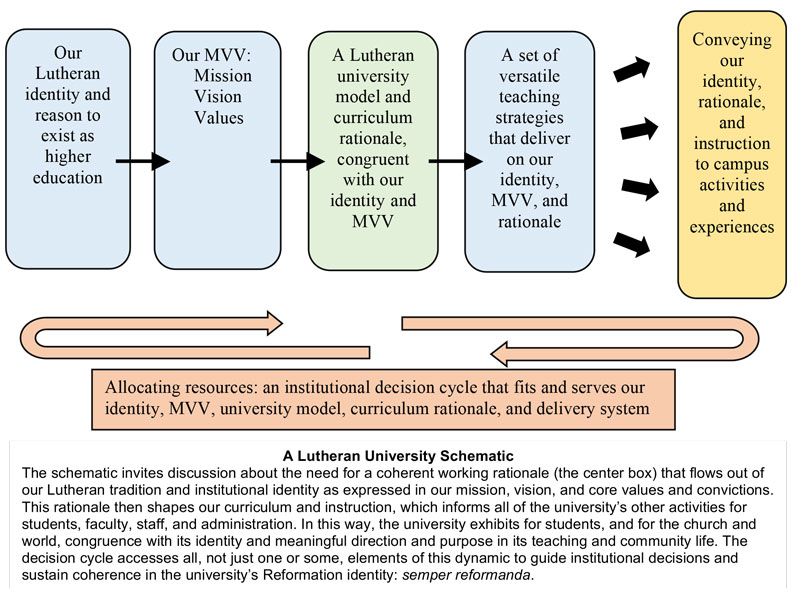

- Our young faculty member has a clear understanding of our Lutheran University Schematic noted above. She sees how the university MVV is conveyed to students through her work and the work of her colleagues in meaningful and practical ways that connect students to the university’s raison d’etre.

- Our faculty member will develop an increasing command of her discipline both in its content and in its role within God’s left-hand kingdom. In doing so, she designs and delivers her instruction not simply within her own or her discipline’s knowledge base, but as an essential part of the university’s rationale for its development of more highly educated Christians in our culture. Such an approach will likely require some mentoring from her colleagues since, depending upon our professor’s graduate school training, her terminal degree may have been attained in a “multi-versity” setting (see the higher education models above). In the Lutheran Christian ethos, the academic discipline is valued, but, to paraphrase Paul, when it comes to understanding the place of a disciple in Christian higher education, our faculty member will embrace a still more excellent way (1 Corinthians 13:1).

- Our faculty member also gains an increasing command of the biblical narrative and the Reformation’s insights on the Gospel. She likely already has a good understanding of the doctrine of justification and the centrality of Christ. She will further form her teaching and work with students by deepening her understanding in several of the Reformation’s insights about the Gospel such as those themes we mentioned earlier: a biblical anthropology of human nature, vocation, Christian liberty, and God’s two kingdoms. Or, our professor may want to explore other or additional Reformation themes, some more germane to her discipline, since they all overlap across God’s two kingdoms.

- Given our culture shifts and our 21st century students, our faculty member will acquire a working understanding of other theological traditions and non-Christian worldviews. Students bring to us the usual questions and uncertainties about truth claims, ontology, ethics, and human relationships. Often, these issues are already embedded in our discipline content. Where the college experience model addresses these matters only in a piecemeal way, and the multi-versity not at all (unless they are the topic of a particular class), our professor and her students deliberately attend to these concerns as part of the rationale and deep learning of their university. She will need to include this formation first for herself, then for her students. While a multi-versity may regard professional development as something desired only within one’s academic discipline, the Lutheran university will support and facilitate her development in its Reformation distinctives.[25]

- Our faculty member will also explore, practice, and refine her teaching modes, that is, her methods for bringing together for students their course content and university activities with the university’s MVV and theological tradition. Much has been written on teaching and faith intersection and integration, some helpful, some less helpful.[26] During her first years of teaching, our professor will examine and discuss with colleagues these teaching modes, with attention to both God’s left-hand and right-hand kingdoms which are always in tension with each other. Moreover, the Lutheran university may well make a part of its faculty evaluation process some inquiry of what our professor is exploring in her reading and study of the Christian faith and the ways she intersects and integrates its ethos for her students.

Without this formation or something like it, we too easily default to other sources and norms for our higher education such as whatever is current in the Chronicles of Higher Education, the conventional version of the college experience, or what we’ve always thought. And the Lutheran tradition may not be what we’ve always thought.

Faculty formation, however, is not just personal and individual. Equally or more important, students in a “post truth” culture need exposure to a community of scholars who can articulate, explain, and apply their tradition and its coherent rationale in ways that students can see are not just arbitrary or personal and private. Otherwise, “It’s just that professor’s opinion.” The faculty will put in place a pattern of opportune yet challenging ways to continue their formation as a faculty such as forums and table talks, reading groups, visiting scholars, colloquy studies, enrichment seminars, extended orientation for new faculty, and release time and sabbaticals.

It’s a truism: we do what is important to us. If we don’t do these things, plainly they are not important. If the university actually intends to put its MVV to work for students, for its constituency, and for the world God so loves (John 3:16), then it needs to form a faculty to do that work. Not all members will be able to participate in all formative activities at every time they are offered (due to graduate studies, family circumstances, and other conditions), and we don’t want to turn this formation into pietism or legalism. But we do want to create opportunities and positive expectations for cultivating over time a faculty that delivers on our mission, ministry, and biblical convictions.

The university’s evaluation process may find that a faculty member is resistant to participating in such forming and re-forming activities, or resists taking them up in some other meaningful fashion for himself or herself. If so, then caring colleagues in the evaluation process need to approach the faculty member patiently, wisely, and evangelically (and certainly avoiding legalism or ultimatums) to help this fellow Christian consider whether another position or direction in Christian vocation might be more appropriate. However, the faculty member’s willful neglect of such forming and re-forming practices should, in all ways appropriate, be addressed as self-excluding and incongruent with the faculty and university’s rationale. Simultaneously, the institution itself should be open to healthy critiques from faculty members who regard their self-exclusionary practices as reasonable and not in contradiction to a Lutheran ethos, even as Jesus—not uncritical of organized religion—did not participate in every practice of the “religious” people of his day.

The Delivery Vehicle

Christian faculties and universities do a lot more than academics, and they should. Academics and non-academic activities are not mutually exclusive, and academics is not intrinsically more valuable than other experiences. We want to provide our students with a wide range of experiences by which they learn to love God with heart, soul, mind, and strength. We do this not with a college-experience model but with a coherent rationale that orchestrates those experiences in ways which are not haphazard and buffet-style. We’re not running a Walmart.

But undergraduates tend to think so because they are accustomed to Walmart, where consumers can drop in their carts what they prefer and ignore the rest of the merchandise: “Why do we have to take all this general education stuff, anyway? Just let me take classes in my major.” Of course, if their general education curriculum is incoherent and little more than a buffet, they have a point. If, however their faculty has crafted a genuine curriculum for their university which presents a tradition that has been hammered out, disputed, examined, and has held up for centuries because it’s grounded in the orthodoxy of the historical church, then our undergraduates have some things to learn. As undergraduates, they aren’t equipped to re-invent in four years an entire tradition and then figure out how to apply it on their own. That’s why they need a faculty—not as “guides on the side” but as guides up front who already know the territory, know what they’re talking about, know where we’re all going, and can deliver on it. (For the reader not yet acquainted with the perennial general education controversies, see a concise history and discussion in Louis Menand’s book, The Marketplace of Ideas.[27])

To further appreciate our delivery vehicle, consider one more difference between the college experience model and the university model. Luther worked out the distinction between Christ in us, in nobis, and Christ for us, pro nobis, and realized that Christ is always first outside of us (extra nos) and for us prior to in us (see, for example, 2 Corinthians 5:17-19; Romans 5:12ff.; Colossians 2:13–15). This subtle but critical distinction alerts us to the danger of looking inward for our identity, for our well-being with God, and for our vocation regarding neighbor and culture—as if God is first in nobis. Such inwardness leads us only to our own sin. Christ crucified and risen is what God has done outside of us and for us sinners—pro nobis—and He is our genuine source for identity, our well-being before God, and our confidence for ministry to the world (cf. 2 Corinthians 3:1–18).

But the college experience model assumes and promotes an in nobis orientation: student-centered on the post-adolescent’s subjective experience of chiefly self-selected preferences that are personal, individual, and emotive. By contrast, the university model directs the student away from self to an already historically worked-out and rationally sourced set of arguments and convictions about life and reality located in the university’s Christian, Lutheran tradition and its teaching. [28]

Academics—including the curriculum and all our additional means of teaching—is the vehicle for delivering our rationale for faith, learning, and formation not just to students but to the entire university and all its activities and experiences. Why so? Academics is our means for articulating, explaining, and understanding all that we do in dimensions that are “not flat but deep.”[29] It’s our delivery system for our Lutheran edition of higher education, an edition that relies on a set of less-than-easy (and often counter-intuitive) theological insights. Students and co-workers recent to the campus do not arrive with or initially grasp these themes and insights. We, of course, are not practicing some form of elitist Gnosticism to which only a few privileged souls can gain access. As our higher education ministry of the Gospel, we seek to include as many as are able and ready to be more highly educated in this ethos and formation.

Our academics inducts them into ways of thinking, reasoning, and understanding that will form them as educated Christians who can effectively live out their vocation and not just drift through life with a few religious aphorisms and a lot of random experiences. C.S. Lewis makes this pointed observation about the educated Christian: “To be ignorant and simple would be to throw down our weapons, and to betray our uneducated brethren who have, under God, no defense but us against the intellectual attacks of the heathen. Good philosophy must exist, if for no other reason than because bad philosophy needs to be answered.”[30] Rather than merely conforming to their culture, these more highly educated Christians are then prepared to offset their culture with a counter-cultural theology of the cross, all in service to their neighbor.

Conclusion

What will it take to promote and sustain the formation of faculty? Such formation will need the commitment of the university. But, of course, if the university is a Lutheran university, it has in its MVV statements already committed itself to do this. Formation can be fruitful at a small scale among a group of colleagues, in a department, or in small reforms in the curriculum. And perhaps it happens best this way, like seed scattered upon the ground that slowly grows, we know not how (Mark 4:26–29). Or perhaps, because the university is an institution, and institutions are instituere, set up or established to stand for something, the president is the one who takes a stand. He stands as our brother, colleague, and paraclete for the model and rationale that connects our MVVs to our students by means of the university’s delivery system. Either way, or both ways, “Oh how good and how pleasant it is when we dwell together in unity” (Psalm 133:1).

Response 1: The Theology Department and a Faculty for Lutheran Higher Education

Charles Blanco, Ph.D., Concordia University, Nebraska

A few words may be added here regarding the role of the Theology Department in view of this article on Lutheran higher education. In the multi-versity model, a Theology or Religion Department would be a stand-alone academic discipline having the same status as any other department or discipline. Except for perhaps a one-course engagement through a general education component of a curriculum, a student at a multi-versity approach toward Lutheran education would have very little intersection with the Theology Department. It should be obvious (but it’s not!) that if a student can be “done with” Theology after the first semester of the first year, such a curriculum has very little claim to delivering a Lutheran higher education regardless of its lofty MVV statements.

Similarly, in a college experience model (particularly one that has suffered “culture capture” such that the experience of college is a time of one’s prodigal journey to the pig pen), the Theology Department that strives to engage students with the faith that was once for all delivered may likely be seen as an annoyance. “I came here to party, not to have some class foist its antiquated view of morality upon me!” It can also be the case that if a school successfully recruits students to attend a distinctively Christian expression of the college experience, those same students may be flummoxed to discover that taking a Theology course involves work, study, and disciplined thought, engaging profound thinkers across multiple millennia. What is the role of the Theology Department in the college experience model? Is it Christian counseling? Providing pastoral ministry? Serving as vocational guides? It is easy to see how a college could want to deploy its theologically trained faculty to enhance the college experience of its tuition-paying students.

In a genuine Lutheran university, the members of a well-formed and regularly re-formed (semper reformanda) Theology Department would serve as a critical asset not only for the students they teach, but also for all other academic disciplines as well as for staff and administrators. It would not be the case that the Theology Department holds the “right and final answer” for every question that arises in higher education. Rather, assuming that the department members are well-educated in the Reformation distinctives (referenced above and widely available through many sources), our Theology colleagues would have humble but meaningful contributions to make as the university sought to live out its MVV statements

In this university with its faculty formation, strong theological minds would certainly be active in other departments on campus, and a well-formed and regularly re-formed Theology Department would rejoice in such a state of affairs. Yet, it could and should never be the case that in a Lutheran institution of higher education that the Theology Department is allowed to become simply another academic department. Its members should be recruited not only for their academic expertise and excellence, but also, and perhaps primarily, for their understanding of and their ability to apply the foundational features of Lutheran theology to the contemporary scene across a wide variety of disciplines.

In a genuine Lutheran university, the members of the Theology Department would have an obligation to maintain collegial relations across the various domains of the campus. They would ideally be seen as “not without which” resources for consultation for key decisions in campus life. (See the decision cycle in the Lutheran University Schematic.) Again, we need not imagine that the department members would hold veto power or would be seen as “the debaters of this age.” Rather, as those who have dedicated their lives to exploring the intersection of theology with the whole of life, they would be seen as allies in a position to offer helpful insights and prudent counsel so that when decisions are made within the university, these decisions are truly congruent with the underlying theology of the university’s MVV statement.

To accomplish these goals of a Lutheran university, such a Theology Department would need to be well-staffed and well-resourced. By contrast, in a college experience model, the staffing of the Theology Department would rank equally among all other concerns of the university. For example, if an adjunct professor could step in for a first-year writing course, then certainly an adjunct professor could step in for a general education theology course, provided that this professor offered a good experience for the student.

We may grant that a carefully selected adjunct could fill such a role in a genuine Lutheran university. Nevertheless, that instructor would in fact and in effectiveness be adjunct to the fully staffed and fully formed Department of Theology that was called and well-equipped to enable the University to carry out its MVV statement. It would, perhaps, not be an overstatement at a genuine Lutheran university to say, “As goes the Theology Department, so goes the University.”

Response 2: The Faculty, the Liberal Arts, and Models of Higher Education

Gabriel Haley, Ph.D., Concordia University, Nebraska

A Christian education, if it means to suggest at all that theology has a bearing on the other disciplines, is de facto a liberal arts education (an earlier response makes a similar point). To say that theology has anything to do with physics or with literature or with health sciences is to say that there is a connection between discreet bodies of knowledge. This is the assumption of a liberal arts education. Now, Christian institutions can be more or less aware of this foundational assumption. The more aware they are, the more it will influence their structure and curriculum.

The great defender of the liberal arts university, John Henry Newman, attempted to make this warrant explicit at a point in history when institutions of higher education believed they could retain a liberal arts curriculum without theology. Newman argues that the academic discipline of theology is the very field that engages the metaphysical claims that provide the bonds between disciplines. If it doesn’t do that, some other discipline will try, inevitably going beyond its proper disciplinary boundaries. Nineteenth-century institutions believed at their core in the value of a liberal arts education, but they were starting to doubt the need for theology. Newman’s Idea of the University maintains that you can’t have one without the other.

C. S. Lewis’s The Abolition of Man, cited admiringly in the article above, makes a similar argument, yet with special attention to how modern educational methodology can undo philosophical assumptions that are taken for granted. Lewis targets modern educational trends that were beginning to isolate a student’s feeling-response as a singular point of interest. Today, we might call this an emphasis on “self-expression.” But what begins as a seemingly humanistic effort to celebrate the individual finds its end in undermining the value of all human feeling-responses. Lewis’s argument, in short, claims that by isolating the feeling-response, we end up detaching feeling from purpose. The teacher that, perhaps innocently enough, encourages students to “self-express,” without ever offering the possibility that some feeling-responses may be more valid than others, ends up devaluing self-expression. When all feeling-responses are arbitrary, none can persist in holding validity or value.

What often happens, particularly at the level of higher education, is that these feeling-responses start to be observed at a distance. They become objects of analysis. Since every feeling-response is seen as idiosyncratic and arbitrary, the result is that this affective data becomes the object of suspicion. What is sometimes called “critical thinking” can mean this kind of aloof suspicion of other people’s perceived prejudices. Lewis calls this the process of “debunking.” (It must be noted that “critical thinking” is a goal of education for Lewis, but “critical thinking” must not only mean a hermeneutics of suspicion.) By detaching itself from a “doctrine of objective value”—which Lewis calls the Tao, meaning “the Way”—modern educational methods diminish the special status of the human being. Humans become data points. A sense of higher purpose is lost.

So whether the priority is on “self-expression” or “critical thinking,” modern education has ripped emotion away from its proper orientation toward objective value (and notice here that Lewis is seeking to retain a traditionally theological stance, that of objective value). Moving away from a belief in objective value has the dangerous consequence of making students more easily manipulated, as they fall prey to the political and social whims of the day. As Lewis argues: “Either we are rational spirit obliged for ever to obey the absolute values of the Tao, or else we are mere nature to be kneaded and cut into new shapes for the pleasures of masters who must, by hypothesis, have no motive but their own ‘natural’ impulses.” Lewis prefers that education educate—it must lead us out of our own limitations and impulses, individually and as a society. Educators must cultivate noble emotions in students. We must stoke a desire for truth using every disciplinary resource we have. And the only way to do that legitimately is to uphold a doctrine of objective value. This doctrine is properly upheld by the academic discipline of theology in a Christian university, yet other courses can be intentionally crafted to use their own disciplinary resources, like ethics and aesthetics, to participate more fully in a Christian education.

Christian education is thus de facto a liberal arts education, not an “experience” (as defined in the article above). In fact, Christian education may offer the best rationale for the liberal arts. Christian institutions of higher education will become more themselves the more they fortify their status as bastions of the liberal arts.

Response 3: Ten Comments and Questions

Brian Friedrich, Ph.D., Concordia University, Nebraska

- As acknowledged in the article’s opening note, the article may attempt to cover too much ground in one bite. Perhaps two separate articles, “A Model of Higher Education for the Lutheran University” and “A Faculty for Lutheran Higher Education,” would allow the author and the readers to explore the issues more deeply.

- In the early paragraphs, the writer uses the term “culture” in a seemingly generic sense. Would it make sense to further define and clarify the concept of culture? For example, how does the use of “culture” in the article relate to “worldview”? Does the use of culture apply to a distinctive U.S. culture of the 2010s?

- Is the current culture “now ambivalent toward religion,” and “no longer defers to a Christian perspective” different today only by degree? Or is it yet a new version of a broken culture that has been with us since the angel blocked Adam’s and Eve’s re-entry to the Garden of Eden? Depending on the author’s answer, should additional definition or explication be given?

- Nationally, non-traditional students (working adults) now comprise about 50 percent of the undergraduate population. And “generally smaller” institutions (see the list of the five models) now have graduate, online, face-to-face, and hybrid programs. Should these realities be taken into account when discussing the models?

- The first half of the article emphasizes Christian (or Lutheran) college; the second half of the article emphasizes Christian (or Lutheran) university. Is the writer’s intent that the reader understand Christian college and Christian university as one and the same and, thus, the seeming interchangeable use of the two terms? Or are we to associate “college” with the college experience and “university” with the schematic diagram’s attention to a unifying rationale?

- Who owns the institution’s Mission-Vision-Values statement? Isn’t the MVV “owned” by the collective institutional community? Ownership of the MVV is equally that of the faculty, the administration, the board, the alumni, and all our constituents.

- It seems that the MVV should ultimately be the sedes doctrina that answers the question of “which model.” If we read and take seriously our MVV, will the proper and congruent model emerge naturally? Or, in the context of this article, is it possible for a Lutheran institution of higher education to apply its MVV to either a college experience model or a university model?

- The article raised a new question for this reader. Should we be calling and appointing faculty in order to form them? Or should we be calling and appointing faculty who are, in general, already formed in our understanding of Lutheran education but need be intersected into our specific Lutheran, Christian community?

- When Dwight Eisenhower was serving as president of Columbia University, the anecdote goes that his faculty put him on notice: “Mr. President, we the faculty are the university.” If that assertion is correct, at least in part, we can continue to wonder what is the faculty’s role in collectively agreeing upon “the model” and “the vehicle” and the “formation” of itself.

- The Conclusion suggests that the president must take a stand regarding “what it will take to promote and sustain the formation of the faculty.” However, I am not sure this is enough. The president may well need to be the proverbial point of the spear, but without the ownership of the board, the faculty and the entire administration, I’m not sure the president will be able to accomplish the task as it ought to be done. It needs to be a collective effort.