Complex Nature-Nurture Sin and a Gospel Perspective

Russ Moulds, Ph.D., Professor of Psychology, Concordia University, Nebraska, rmoulds@cune.edu

Is speaking English genetic? Is heterosexuality a learned orientation and behavior? Are all people either male or female? Does the Gospel, which is the power of God for salvation for everyone who has faith (Romans 1:16), rescue individuals from homosexual orientation and practice (LCMS Synodical Resolution 3-12A, 1992)? Is nature still what God originally created it to be in Genesis 1? The Lutheran tradition sustains a creative and dialectical tension between God’s right-hand kingdom and God’s left-hand kingdom. Our biblically informed views on LGBT issues, then, are informed also by what the sciences now tell us and do not tell us about these matters.

This article will identify four key areas of study in what is called biopsychosocial research that can help us appreciate the protracted confusion about gender and LGBT issues. Awareness of this research assists the church and our ministry in three ways. First, this work in God’s left-hand kingdom can shape how we teach about these issues within the church and in the public square. Second, awareness of this content will help us better understand and care for the human situations that we encounter in terms of what we will here call “complex nature-nurture sin.” And third, these areas of research inform our understanding of the human condition and assist us with applying the Gospel as God’s response to our fallen state in all its manifestations, including heterosexuality and homosexuality.

Some Instruction

In 1995, responding to student interest in genetic and brain research reports in the popular press, I created a unit of instruction on homosexuality for our Psychology 101 course. This curriculum describes the hypotheses and lines of inquiry that have sought—without success—to explain homosexual orientation and behavior and the current state of the research. The unit then examines compassionately this atypical but significant aspect of the human condition in terms of God’s words of both Law and Gospel. With updates, this curriculum is now 20 years old, and I have presented it to thousands of students and other interested groups at conferences and congregations. They have found it helpful.

When I first began teaching the unit in the 1990s, I had to weight the presentation and discussions a bit toward mercy. Most participants were conscientious young Christians and were not especially condemning toward gays and lesbians, but they were wary. The AIDS epidemic was at its peak, the biblical texts on same-sex relations were clear to them, and gay pride was not yet a cultural norm. While these participants did not share the vitriol expressed by most of their culture and many in the church at that time, they did tend to isolate homosexual behavior for selective condemnation from our larger fallen and sinful condition. Their basic perspective was, “Hate the sin, love the sinner” with a moderate emphasis on “Hate the sin.” This perspective did provide a workable starting point to acknowledge same-sex relations as sinful while expanding their view to the larger postlapsarian context of all sins of thought, word, and deed. We could then discuss the biblical theme of grace, consider the evangelical content pertaining to homosexuality in such study documents as, “Human Sexuality: A Theological Perspective,”[1] and explore possibilities in sanctification for sinners of all sorts.

Twenty years later, the majority perspective for my participants in class and presentations regarding gender and LGBT issues has shifted to “Love the sinner because we should be nice and not judge others”—not surprising, given the cultural shift and the popular perception of religion as judgmental moralism.[2] I now have to frontload the presentation somewhat more toward our discussion of sin, a fallen creation, and God’s word of Law. This serves as preparation for appreciating divine grace and spiritual growth rather than settling for some transient version of social tolerance or capitulating to any current politics of radical gender identity. The cultural landscape has changed, and our teaching ministry must adapt, just as Paul adapted his ministry while sustaining his aim in the Gospel. (1 Corinthians 9:19–23)

Nature, Nurture, and Causation

Can the research in the sciences of God’s left-hand kingdom help us with our teaching ministry? Yes, but before we examine those four areas of the biopsychosocial research, we must first note an important gap in all the LGBT research: currently we have no biological or neurological explanation for homosexuality as an affective orientation or as a psychological drive. To put it plainly: while all our nature-nurture conditions have multi-factor causes, the sciences cannot tell us what multiple factors cause someone to be gay or lesbian.[3] Twenty-five years of studies have indicated some curious patterns in the incidence of homosexuality. For example, if one identical twin brother is gay, a significant correlation exists that the other brother will be gay but not a 100 percent correspondence. This correlation indicates a genetic component while leaving open the influence of nurture and environment. Another interesting finding is that homosexuality in men is correlated to their having a greater number of older brothers, whether homosexual or heterosexual. Despite these and other findings, causation remains an unknown and, for reasons we will consider below, is likely to remain unknown. This knowledge gap is no longer news, but many participants in the discussions remain unaware of it.[4]

Given this absence of any causal explanation for sexual orientation, the cultural LGBT discussions in both the popular press and academic journals have now turned from the choice-or-born-that-way debate to contingencies in biology and genetics, development, and environment. For example, a standard search of the Academic Search Premier database for 2010–2015 lists only seven articles related to causation but 48 studies about social attitudes, identity, and behavior. While choice about sexual conduct remains an important topic, the church needs to be aware of the research and not perpetuate claims regarding choice in sexual orientation about which the research is clearly inconclusive.

Rather than treating homosexuality only as a matter of moral choice, we can appreciate the complexity of the LGBT issues by considering Paul’s opening chapters in Romans. Paul devotes the entire first part of his letter to the disastrous consequences of sin on everything human. However we may exegetically handle the same-sex material in Romans 1:24–32,[5] chapters 1–5 catalogue a devastating inventory of the toll sin takes. As James perhaps anticipated Paul’s insight, “Whoever keeps the whole law but fails in one point has become guilty of all of it” (James 2:10). No one escapes judgment apart from Christ’s atonement. In Romans 8:20 and 22, Paul then expands this catastrophic theme, writing that “the whole creation was subjected to futility” and “has been groaning in travail.” Thus, sin affects not just our moral behavior and our moral reasoning but everything else including our biology, our rationality, society, and the environment of creation. We can help our congregations and classrooms better to understand these pervasive effects of the fall on humanity, including our sexuality, by alerting them to four areas of study about nature and nurture.

Four Levels of Complexity

We begin with 1) the neural complexity of the brain. The neurosciences have advanced rapidly over the past two decades through research in brain imaging and microbiology. Information about brain studies is now common in the popular media, but the brain basics remain astonishing. Roughly speaking the brain has about a hundred billion neurons. Depending on the type, that neural cell can make upwards of ten thousand dendrite connections with other neurons. And those neurons use more than one hundred different neurotransmitters to chemically communicate with each other. These three factors alone allow mathematically for (1011 x 104 x 102 = 1016) different neural combinations. While certain principles of brain architecture put limits on this number and give us all a standard brain structure (in many respects we are not all that different), the potential number of different “setups” for temperament, personality, and behavior allow for important dissimilarities. Meanwhile, many of our most common features remain a complete mystery. For instance, we still have no explanation for why most of us are right-handed (Latin, dexter), but some of us are left-handed (Latin, sinister).

Next we consider 2) the Human Genome Project. When the Project began in 1990, geneticists expected to map about 100,000 protein-encoding genes in our DNA. Early on, researchers were pondering whether even this number could account for our complex behavior and different characteristics. If we all share the same DNA, chromosomes, and genetic code, wouldn’t we need a lot more “Lego blocks” to explain variations in traits and behavior? When the mapping was completed, project scientists were stunned: the number of genes turned out to be about 20,000—the same range as a mouse. Our having the genetic range of a mouse doesn’t much sound like, “Thou hast made him little less than God” (Psalm 8:5). How can our heart, soul, mind, and strength reflect the very imago Dei? And how then does the human body have so many different kinds of cells and organs in the body and, remarkably, so many different kinds of neural structures and networks in the brain?

This puzzle takes us to 3) the ENCODE Project. To appreciate the significance of this research, we need to recall the famous double-helix structure of DNA. DNA molecules are made of those two twisting strands joined by “ladder rung” links called base pairs composed of nucleotide molecules labeled G, T, C, and A. We know that our genome contains approximately three billion base pairs. The Human Genome Project mapped the coding genes used by the DNA-RNA process to replicate the various proteins which form our different tissues such as skin cells, liver cells, and brain neurons. But the ENCODE Project has confirmed that only about 10 percent of our DNA consists of these coding genes. So the ENCODE Project researches the role of the remaining 90 percent of the genome which previously was regarded as “junk DNA.” We now understand that much of this non-coding DNA is not junk but is functionally involved in the regulation of the coding genes. These regulatory functions include a number of complex processes such as switching systems and folds in the molecules and are far more complex than had been expected. Disruptions in the regulation of gene activity and protein production result in anomalies in cell processes. And with three billion base pairs and multiple functions involved in continuous replication and cell reproduction, things can sometimes go wrong. Or different. Or atypical.

How so? Researchers are exploring some answers in the study of 4) epigenetics. Coding genes are not always active. Their protein-generating operations get “switched on and off.” Some of the switching systems are internal to the DNA and are managed by that other 90 percent of the genome. But genes are also turned on and off by epigenetic factors, that is, external environmental elements that act upon (epi) the coding genes and the other DNA regulatory functions. These influences include such factors as nutrition, toxins, and even the weather.[6] Geneticists have long been aware of epigenetics as a concept. Some set of dynamics has to act on and determine the role of a not-yet-differentiated stem cell—each with the same 20,000 coding genes—that has the potential to become any kind of cell the body needs. But only in the past few years have researchers begun to decipher the switching systems and detect a few of the environmental factors that turn coding genes on or off. Depending on when and which genes get turned on and off, the results can be imperceptible but can also be dramatic. Epigenetic influences have been demonstrated in studies on cognitive development and cancer, are being investigated in autism and stress and hypertension, and appear to be implicated in predispositions for depression and addiction. The research understandably pursues an emphasis on disease, but on the positive side, epigenetics is also being applied to studies in immune system resiliency and in temperament and personality.

The Fall and Its Fallout

Relevant to our discussion, of course, is how these four areas of study inform our understanding of atypical sex orientation and gender dysphoria. The “nature versus nurture debate” is no longer a debate. Nature and nurture constantly combine throughout development and even across generations, sometimes to determine our characteristics but also to influence our cognition and conduct in complex and subtle ways. For this reason, the choice-or-born-that-way debate about homosexuality has been set aside, and research projects dedicated to locating a cause for homosexuality are few.

Instead, we can apply more nuanced but plausible ways to consider LGBT nature-nurture issues, all in the context of creation and fall in Genesis 1–11 and sin and grace in Romans 1–11, followed by Paul’s conduct content in 12–15. A tableau for both heterosexuality and homosexuality begins with God’s very good creation that includes the human genome. The picture also includes the fall and our recognition that nature, including the human genome and all its processes, is no longer what God originally created it to be. Genesis 4–11 broadly but vividly sets out the comprehensive consequences of sin on all of creation.

The sciences enable us to explore these consequences and the human condition in less-than-complete yet helpful ways within God’s left-hand kingdom. In these ways, we exercise vocation and serve our neighbor, acting as stewards of all that God continues to entrust to us. As stewards of this left-hand kingdom knowledge, we understand that the genome and its replicating systems are complex beyond our current ability to describe, that the processes work well, but that the processes are susceptible to internal and external influences which lead to atypical results—sometimes unimportant, sometimes harmful, sometimes different. Most children are born anatomically male or female, but a few (1 percent or less) are born with genitalia that doesn’t match their XX (female) or XY (male) chromosomal sex. This outcome can occur due to assorted aberrations in the child’s prenatal development, but the most common cases result from a genetic condition in the mother by which she produces excessive masculinizing hormones and passes them to her female child in utero. The XX female exhibits ambiguous genitalia, a generally male appearance, and masculinized behavior. Though this maternal condition called Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia (or CAH) is now understood, little is known about its underlying causes.

And these sorts of conditions and outcomes bring us back to the genome, the coding genes, the regulatory DNA, the internal and external switching systems, epigenetics, and the neural complexity of the brain. A lot can go right, wrong, and sideways. Or, as the Psalms say, “Thou didst knit me together in my mother’s womb … wonderful are thy works” (Psalm 139:13,14) and, “Behold, I was brought forth in iniquity, and in sin did my mother conceive me” (Psalm 51:5). In this sense we can help our congregations and classrooms think about complex nature-nurture sin—not sin in the sense of “doing bad things” or moral turpitude (though this, too, may be part of any discussion about sinful humanity) but as our fallen sinful condition in which we are all vulnerable.

Eden and Calvary

As noted earlier, the research has not yet arrived at any causal explanation for homosexuality or other LGBT conditions. We do have a biblical framework for understanding that our sinful human condition distorts sexuality, including heterosexuality: “But I say to you, whoever looks at a woman lustfully …” and “Whoever divorces his wife …” (Matthew 5:28, 31). And we have a research framework for better understanding some dimensions of our human condition. The processes in genomic replication and cell division are not always entirely precise. These processes can be influenced and altered by both biological and environmental factors, particularly at critical periods in prenatal and perinatal development. And these critical periods of development are especially important for the neural complexity in early brain organization. None of us is genetically determined to speak English, but our language neural networks are already being set up prenatally by genetic and perhaps epigenetic processes we don’t yet grasp. If, due to some context of deprivation—deprivation being part of our post-Eden condition—we do not learn any language by about age 12, our brain will no longer be able to learn to process any language in a typical way because its critical period of development for language has now closed. Typically, experience “loads” those language structures of the brain with a native tongue such as English or Spanish. Our language behavior then becomes so integral and irreversible to our being that, if we didn’t know better, we’d say it was genetic.

Our sexuality is similarly integrated into our being in multiple and complex ways including our biology, anatomy, neurology, gender roles, and social structures, all of which are now distorted by sin. What issues does this raise for Christian education? Many of our students and other fellow Christians now tend to perceive an LGBT life as merely circumstantial and a matter of personal disposition. Their perception lacks a reference to the Scriptures’ framework for our sinful human condition as the object of God’s condemnation in need of Christ’s radical intervention on the cross. This perception also informs their outlook on heterosexuality, cohabitation, marriage, and divorce as matters of contingency—perhaps unfortunate or perhaps merely personal preference—but, in their view, “just the way things are,” without their studied attention to Eden or Calvary. Some of our colleagues and other fellow Christians tend to regard an LGBT life only in moral terms and a matter of personal and political choice, without attention to complex nature-nurture sin and without much reference to the Scriptures’ compassion for our human frailty. By contrast, Paul concludes his case for sin and grace for both Jews and Gentiles in Romans 11:32 by insisting that “God has consigned all men [not just some of us] to disobedience that he may have mercy upon all.”

To assist with addressing these perceptions, we conclude with a summary sequence of ten presentation and discussion items on LGBT concerns in terms of both complex nature-nurture sin and a heart for the Gospel. These topics can be expanded, adapted, and varied for discussion and disputation according to the needs and interests of participants. They have proven useful for helping others consider and reconsider our culture’s views about LGBT past and present and their own ideas about creation and fall, and sin and grace. The writers and editors of this edition of Issues hope our content will be helpful in your reflection, study, and ministry.

A Starter Discussion Sequence for LGBT Concerns[7]

- Homosexuality is sin, that is, it is part of our fallen human condition and our separation from God. (Leviticus 18:22, 1 Corinthians 6:9-10, Romans 1:26-27)

- All sin is the same in that it all falls short of the glory of God. (Romans 3:23) Homosexuality is no different in this sense than any other sin.

- Yet homosexuality, like other sin (especially sexual sin?) has the potential to become a different, distinctly pernicious enslavement to sin (Romans 6, 1 Corinthians 6), perhaps because our sexual identity is so deeply related to our sense of self, and one’s self must be understood in relation to God and His promises, not our desires.

- “Nature” and “natural” are no longer necessarily what God originally designed (Genesis 3:17). Consider for example birth defects, congenital diseases, dyslexia, Tourette’s Syndrome, and violent epilepsy. Notice also that heterosexual male lust is quite natural (postlapsarian) but not good.

- Scripture (and our liturgy) distinguishes among sins of thought, word, and deed. All are sinful. That is, they all diminish our trust relationship with God. That is why they are “bad.” But they have different consequences. Contemplating investment fraud is not the same as depriving others of their life savings.

- An orientation or inclination or predisposition toward homosexuality is not itself homosexual conduct or behavior. An orientation or inclination or predisposition toward male heterosexual lust is not itself rape, adultery, fornication, or even lust.

- We may or may not make choices about sexual orientation. The research is not at all clear about this. But we can make choices about behavior, conduct, what we persist in thinking about, and becoming enslaved to certain forms of sin, whether homosexual or heterosexual. (Romans 6:12-14)

- God does not single out homosexuality for special condemnation. He does, however, take a particularly dim view of moral superiority, spiritual arrogance, and self-righteousness. (Luke 18:9-14)

- We can biblically distinguish between what have traditionally been called “mortal sins” and “venial sins.”

- Mortal sin: willful, intentional and deliberate; these kill faith and drive out the Holy Spirit.

- Venial sin: sins of ignorance and weakness, committed by Christians and daily forgiven for Christ’s sake; these do not cancel our saving faith.

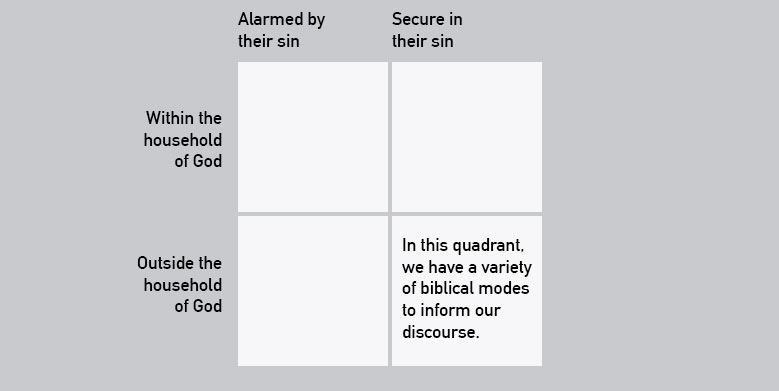

- How the Christian addresses homosexuality, then, depends on whom she/he is addressing. Is that person inside or outside the community of faith (a Christian or not)? Is that person already alarmed by God’s Law and wrath, or is that person secure in her/his sin?

This simple grid can serve as a discussion tool:

- If outside, then we have no authority to compel them in their conduct or behavior. (1 Corinthians 5:9-13) We can, however, invite interest and share God’s Word of both Law and Gospel. (Acts 17:16-34, 1 Peter 3:15)

- If inside, then we have a responsibility to instruct, exhort, correct, and discipline. (2 Timothy 3:16-17)

- If outside but specifically or vaguely alarmed by the Law of God, then we share His Good News with them.

- If outside and secure in their sin, then we point them toward the possibility of something even better than their life apart from God.

- If inside and secure in their sin, then we alert them to their danger.

- If inside and alarmed by sin and the Law, then we speak only Gospel and grace to them.